Where Are You in the Implementation Planning Process?

By Dr. Sobia Khan, Director of Implementation

Note: We have updated our website since this article was published. As a result, you may have been redirected here from a previous URL. If you are looking for the article, "Featured Framework: Implementation Mapping” by Maria E. Fernandez, Tim J Walker, and Aaron Rome please click here.

Many of us are tasked with the role of planning for implementation, yet have very little guidance on how to do this. One of the huge roadblocks we face is that in order to understand what to implement, we need to have both a “thing” that we are implementing and a set of strategies that enable us to implement that thing. You may have heard us elaborate on the importance of selecting the WHAT (i.e., what people need to do differently) and the HOW (i.e., how they will do that thing differently) in our courses and in previous bulletins – these two elements might be considered the basic units of change that need to be identified in order to move forward with implementation. In fact, these are the basic units that are often articulated in what we call evidence-based programs (EBPs) — in an EBP, program developers identify the WHAT(s), select the HOW(s), and test these together to see if the combination of WHAT(s) and HOW(s) are effective. In an ideal world, implementers would have EBPs available to them to understand what the basic units of change are for the kind of change they are aiming to create.

The problem with relying on EBPs to provide guidance on what to implement is that it is impossible to have an EBP for every single change effort that everyone everywhere wants to implement. This means that a small proportion of change efforts may benefit from having an EBP available, while the vast majority of change efforts require development work to understand the basic units of change – the WHAT and the HOW. This is a step that often falls on the shoulders of implementers and yet it is not always explicit that this step needs to be performed. Instead, many of us have subscribed to the “implement and pray” method of developing and implementing programs for a long time.

A better strategy for implementation

It follows that implementers are better off understanding how to develop change initiatives, and then subsequently understanding how to implement them. In fact, we at TCI have differentiated the main processes of implementation into these two categories, and have designed two of our flagship courses around them – Designing for Implementation and Implementation, Spread and Scale. The idea here is first recognizing whether or not an EBP exists for the kind of change you are aiming to stimulate. For example, when I worked to implement tobacco cessation programs for public health units in Ontario, Canada, we knew that a tested, off-the-shelf and manualized program already existed, and used this as our “basic units of change”. In another example, I was recently supporting communities to implement supports for people who have developmental disabilities. Here, there were no EBPs available – and so we knew we had to start with the process of designing for implementation.

When we were implementing the tobacco cessation programs, we went straight into the process of implementation, spread and scale; here, we thought about the implementation team, we built the capacities of the health promoters, we assessed the context and made adaptations to the program to fit the workplace contexts in which we were implementing them. When we were approaching the implementation of supports for people with developmental disabilities, we had to take a step back – what were the things that people needed to do differently, what were their barriers and facilitators to doing these things differently, and what change strategies needed to be used in order to overcome barriers and leverage facilitators? Once we decided on these units of change, we could think about other steps related to implementation such teams, capacities, and adaptations.

Implications for implementation practice

The point here it to be reflective about the stage we are actually at in implementation, and not the stage we think we should be at. Having an evidence-based “thing” that we want to implement is not enough to kickstart the implementation process; we need to identify and select change strategies so we know how change is going to happen. Recognizing our starting point and using the right process model to guide us through the steps of either designing for implementation or implementation, spread and scale, can set us up better for implementation success.

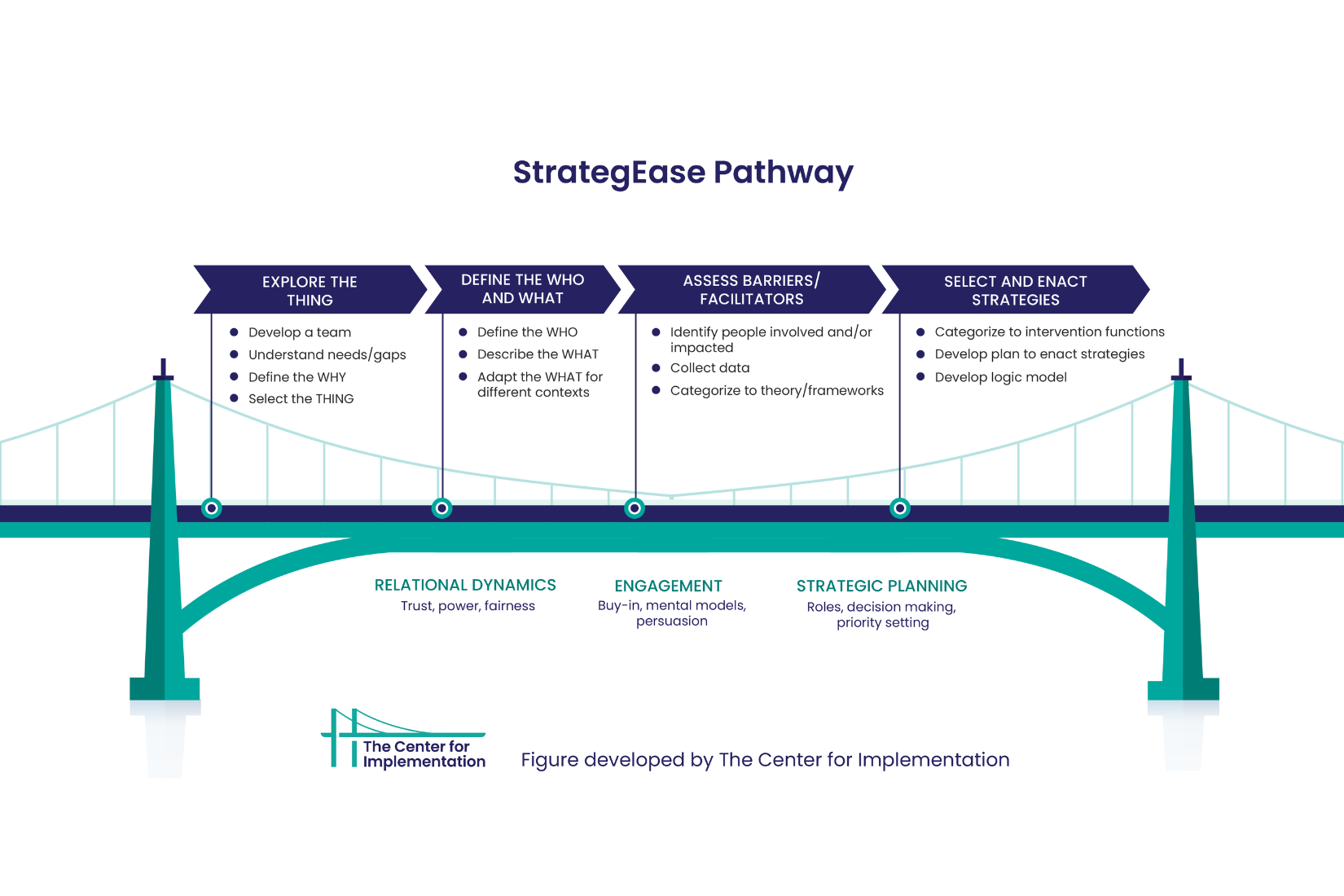

In our last bulletin, we talked about our process model for designing for implementation, which we call StrategEase. This process model is a synthesis of the common steps found in published process models, but adds the steps of articulating the WHAT and the HOW which we find is helpful in both implementation research and practice. One of the process models we used to inspire the development of StrategEase was Implementation Mapping – this is a great process model that offers details on how to select change strategies for implementation.

This article was featured in our monthly Implementation in Action bulletin! Want to receive our next issue? Subscribe here.